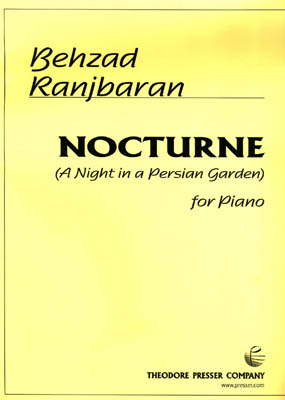

A Night in a Persian Garden is the name of a Nocturne composed by the Persian (Iranian) contemporary composer Behzad Ranjbaran. This Nocturne, published by the Theodore Presser Company in the US, was performed for the first time in 2002 in New York City by the young Persian pianist Soheil Nasseri and has enjoyed many performances by other pianists.

Ranjbaran, born in Tehran in 1955, began his formal violin training at the Tehran Music Conservatory at the age 9. He moved to the United States in 1974, where he attended Juilliard School of Music and received his doctorate in music composition. He is now the professor of music in the Juilliard School in New York City. In 1990, Ranjbaran was named Distinguished Artist by the New Jersey Council on the Arts and received Rudolf Nissim Award from the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) for his violin concerto. His additional honors include a National Endowment for the Arts grant, a grant from Meet the Composer (composer/choreographer project), and a Charles Ives Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

His compositions have been performed by the Philadelphia Orchestra, the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic, Buffalo Philharmonic, and the symphony orchestras of Toronto, Indianapolis, Virginia among others. Last year Delos released Persian Trilogy, recorded by London Symphony Orchestra, a cycle of orchestral works inspired by the stories of Shahnameh. This album was also released by Hermes Records in Tehran.

Unlike most nocturnes that are generally two to three minutes long (like Chopin nocturnes), his fifteen-page nocturne, requires a playtime of approximately ten minutes. The moods that are shaped by this piece revolve around a four-note motive that descends in step-like fashion.

Ranjbaran’s inspiration for this nocturne comes from his childhood memories in Persia. Although there was no effort on his behalf to necessarily write a piece based on classical Persian (Iranian) music, in the opening of the Nocturne one may hear vaguely the sound of santour, or hammer dulcimer, a Persian musical instrument. “The truth is that my compositions are not based on Dastgah (Persian classical mode).

I believe the true character of the traditional music and its quarter tones can only be expressed fully with the Persian instruments. It is more natural for me to be inspired by the color and the overall sound of traditional music rather than arranging the Persian Dastgah for a large orchestra or retuning a piano with quarter tones,” Ranjbaran says. “Of course, this has been done by other composers and has its own merits, but what is important to me is to express emotions and my overall impression of Persian music in my own way than copying the traditional music.

Although I don’t favor the arrangement of Dastgah for a large orchestra or non-traditional instruments, I do believe that an artist should be allowed to express him/herself freely with no censorship. This freedom to experiment allows the artist to explore the possibilities in the creation of different musical styles and instruments thus contributing to the evolution of music as an art form. It should also be noted that today in the world, the higher technical ability of performers in general has impacted the quality of music dramatically.

We should pay attention to the continuous fusion of musical styles and innovations. The experiments and innovations should be allowed and only time would tell which ones would be accepted as the mainstream. I would like to bring up Debussy’s piano work as an example here. Many of his innovations in music were influenced by the use of eastern modes and overall color of eastern instruments. While other innovations have not entered in the vocabulary of the piano, his works are embraced by pianists world wide.”

Returning to the subject of his music and its structure, Ranjbaran mostly composes around small motives with tonal centers rather than writing in a certain key like C major or G major. When Ranjbaran was asked about other Persian composers such as E. Malik Aslanian and Houshang Ostovar, he responded: “unfortunately, for the past thirty years I didn’t have much of an opportunity to hear their work and even when I studied music in Tehran, their work was seldom recorded or even performed, therefore I never had a chance to enjoy their music.”