Translated by Mahboube Khalvati

“Counting on the arts, using the arts, expecting praise and appreciation are the characteristics of those who pretend to be artists and are not the real artists.” – Abolhasan Saba

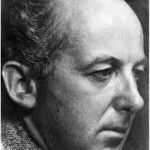

No introduction is needed when talking about the position of the late Houshang Zarif (1938-2020) in the Iranian music. His character and personality are so well-known among musicians that his name per se is a symbol and role model for the Iranian youth. “Becoming Houshang Zarif” is the dream of many young people who enter the world of music in Iran and many of whom retire regretting the realisation of this dream.

Even though he has passed away, it is desirable to open a window to Houshang Zarif’s popular and unobtrusive figure in the contemporary Iranian music and look at his personality.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Houshang Zarif was an unrivaled figure on the music scene, as all the characteristics preferred by the musicians of the time were included in his Zarif’s art. Zarif’s sonority in playing Tar was influenced by three popular musicians of that period: Farhang Sharif, Lotfollah Majd and Jalil Shahnaz.

In phrase composition and composing Avaz phrases, Zarif was influenced by Mousa Maroufi, who taught him to play Tar and to some extent by Farhang Sharif. However, in using the technical properties of Tar, Zarif was under the influence of Ali Naqi Vaziri. It is worth mentioning that at that time Houshang Zarif was the most prominent performer of Vaziri’s pieces; and even today, he is still the most important narrator of Vaziri’s works. In addition to all these characteristics, he had mastered music theory, sight-reading musical sheets and ensemble playing.

Although Zarif’s art of playing Tar owed much to contemporary maestros, the pleasant combination of different styles in playing Tar led Zarif to establish his unique personal style which still has its own fans and admirers today.

Despite all this, Zarif did not seek to attract attentions and spent his whole life working hard for the promotion of the Iranian music in a low-profile manner. Like other members of the National Instruments Orchestra affiliated to the Culture and Arts Organisation led by Faramarz Payvar, he served Iranian musicians by his Tar and his art while avoiding sideline stories. These excellent characters were also possessed by other members of the above-mentioned orchestra; however, in addition to those Zarif had other characteristics which his colleagues either lacked or did not show as much as he did. In more than half a century of musical activities, Zarif was permanently trusted by musicians and always supported them. He successfully passed all the tests of the tumultuous scene of music in Iran.

This is where Zarif’s all greatness comes from; he was indeed simple and humble like a true dervish. He was subtle, witty, and popular. He never used his remarkable technical abilities to enchant the masses. His speech, deeds, appearance and thoughts were always adorned and intended to honor the people.

The role of Houshang Zarif in forming a fundamental criterion in playing abilities of the new generation of musicians, without leading to similarity or even disappearance of personal tones, is unique in the history of teaching Iranian music.

According to one of Tar’s great maestros, those who were not Zarif’s pupils were also influenced by his teaching standards and all learned a little of this style; of course Houshang Zarif’s pupils have repeatedly spoken and written about his spiritual and scientific role in teaching music and his support for them.

Indeed, the responsibility of “being Houshang Zarif” was heavy on every human being’s shoulders throughout the past half century, but Zarif overcame even this concern because he avoided selfishness and this was the secret behind his self-sufficiency.

This article was originally published in Art of Music magazine’s 179th issue.