This article was previously published in Kish Negar Magazine.

Translated by Mahboube Khalvati

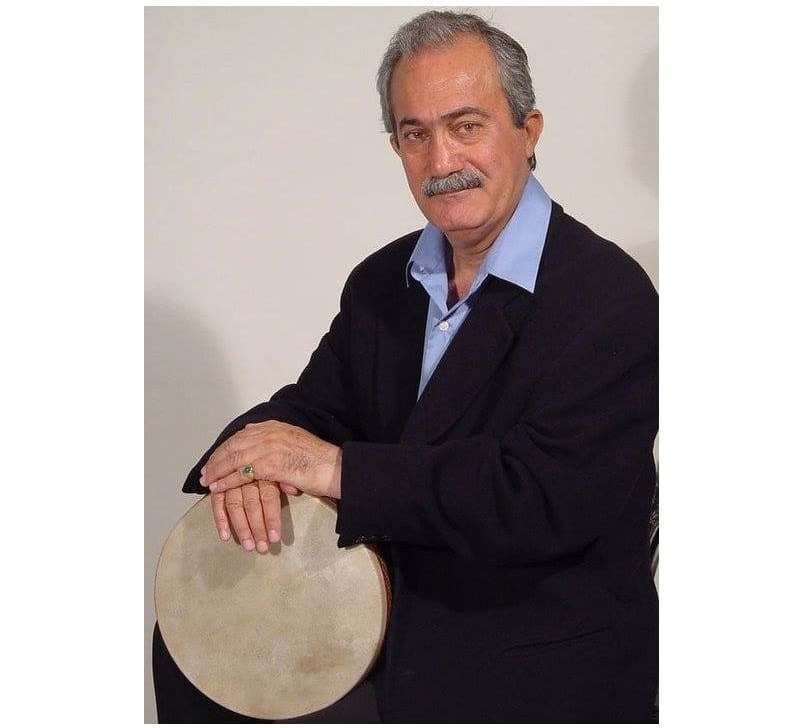

Gholam Hossein Banan was born in 1911 in Tehran. He was born in an affluent art-loving family who were Naser al-Din Shah Qajar (1848-1896)’s relative. The Qajar King was his mother’s uncle on her father’s side. He learnt his first lessons in music while his father sang Iranian avaz (improvised rhythmic-free singing), he then attended classes by the renowned Iranian composer, Morteza Neydavoud (1900-1990) along with his sisters; the composer is, therefore, considered as his first teacher. He then learnt Iranian avaz under the supervision of Mirza Taher Zia Resaee (Zia-o Zakerin) and Naser Seif in an oral manner.

At that time he did not have any knowledge regarding music theory and used to follow the avaz school of the old generation without any attention to his voice type.

Years later Rouhollah Khaleghi (1906-1965) recommended him to attend classes offered by Abol Hassan Saba; hence he became one of the singers of Vaziri School.

Upon first meeting, Saba noticed how talented Banan was. As a matter of fact, Banan’s familiarity with Khaleghi, Ali Naghi Vaziri and especially Saba marked a turning point in his artistic career. Banan enjoyed the consultancy these great musicians had to offer him and became a star in the heavens of the Iranian Avaz.

Specifically Vaziri who had taken classical singing classes in Europe helped Banan to sing within his vocal range rather than singing by pressurizing vocal cords as was the fashion then. Vaziri was then in the lime light for his new proposals and theorizing the Iranian music.

By introducing standards for performing Iranian music, Vaziri directed Iranian music toward a new order. He despised singing with a wrong style and the influence of his ideas on the majority of his fellow singers and musicians is evident. Vaziri paid more attention to his students and the performers of his proposals whose performances had to be perfect examples of his proposals; Banan who was one of Vaziri’s best students.

Gradually, Banan’s avaz which was broadcasted from radio gained popularity among people. Great musicians who worked for the radio and who were Saba’s students composed tasnifs (rhythmic accompanied by singing, an ode) for him. Great masters like Hassan Kasaee and Jalil Shahnaz played the background music for his avaz.

Banan’s two most important colleagues were Rouhollah Khaleghi, Morteza Mahjoubi and Rahi (as lyricist). Banan who was considered as a pioneer classical singer then, had the two favourite instruments of the time, i. e., violin and piano as two accompanying instruments for his avaz. Those years also marked the first experience for using western music instruments and more importantly collaboration with large orchestras. Banan’s avaz with piano or orchestra is best examples of this kind of music to the date.

Banan’s intelligence in singing “Man az Ruze Azal” composd by Morteza Mahjoubi and “Tousheye Omr” composed by Mehdi Meftah when the common avaz practice was disorganized and harsh is admirable. However, wasn’t it for his familiarity with great musicians such as Neydavoud, Saba, Vaziri and Khaleghi, he would have never reached such a high status.

There were several singers of his generation with a wider vocal range and stronger voice, Banan was always ahead of them due to his delicate avaz and his unique punctiliousness.

By the time Banan reached his middle ages, there were many singers working for radio who could compete with Banan in terms of delicacy and attentiveness in performing the music and words. Hossein Ghavami and Mohammad Reza Shajarian (who was Banan’s student) were amng them. Despite this fact, Banan still enjoyed popularity and his style was many’s favourite.

In 1336 Banan lost his right eyesight in a car accident which caused his depression. He continued working as motivated as before though.

Banan’s avaz, whether accompanied by orchestra or a single instrument, is so technical that today few singers can perform vibrations, runs, etc. which Banan can perform. Drawing on his talent, Banan, apart from developing his unique singing style, performed avaz with a single instrument differently from the avaz he performed with orchestra which had a western characteristic.

One of the excellent features of Banan’s avaz is that some of his avaz works, such as “Tabe Banafsheh Midahad,” “Deylaman,” “Amaad Amma” are popular like his tasnifs which proves his talent and deep knowledge in music.

Gholam Hossein Banan, the treasury of Iranian classical avaz, passed away in Iran Mehr Hospital in Tehran in 1982. Pari Banan, his wife, stopped all the clocks in their home as a sign of tribute to him.