Persian Set: Four Movements for chamber orchestra: Moderato; Allegretto; Lento; Rondo

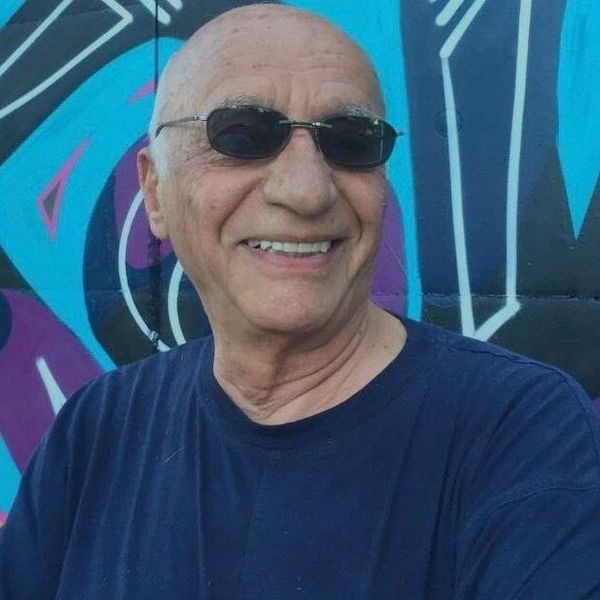

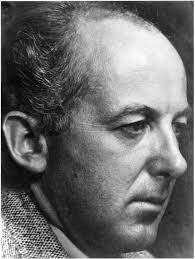

Henry Cowell, one of the most innovative American composers of the 20th century, was born in 1897. Cowell and his wife visited Iran in 1956 and stayed there the whole winter, upon the invitation by the Iranian Royal Family, when he composed his album “Persian Set” in four movements for chamber orchestra. His composition is expressive of the characteristic quality of the Persian or the Iranian music.

Henry Cowell describes below his composition and the general characteristics of the Iranian classical music:

“This is a simple record of musical contagion, written at the end of a three-months’ stay in Iran, during which I listened for several hours nearly every day to the traditional classic music and the folk music of the country — at concerts, at private parties, at the National Conservatory for Traditional Iranian Music (where the instructors gave wonderful demonstrations of virtuosity for my benefit), and at Radio Tehran. Tape recordings at the Department of Fine Arts were especially helpful in displaying the rich variety of music in regions too difficult to visit in midwinter.

“Of course I made no attempt to shed my years of Western symphonic experience; nor have I used actual Iranian melodies or rhythms, nor have I imitated them exactly. Instead I have tried to develop some of the kinds of musical behavior that the two cultures have in common.

“The musical cultures of Asia have remained monodic in theory, but they are often polyphonic in actual performing practice. Attempts to combine the old classic melodic styles of the East with eighteenth and nineteenth century European harmony do not seem to me to be successful. But where a need is felt for the tonal variety of the Western orchestra, I think polyphony (based on the actual structure of the melodies used) is a natural direction for musical development to take in the East.

“The tonal coincidences in Persian Set were suggested by the polyphony actually heard from Iran’s three-to-five man ensembles. In one of the most commonly-heard musical styles the instruments (with or without a vocalist) and the drum take turns leading the melodic improvisation on one of the many inherited formal structures. A second melody instrument then follows the leader more or less in canon, at intervals varying according to his ability to keep up.

Sometimes he will even take off in a parallel but different phrase of his own.

“At Radio Tehran, European and Iranian instruments are sometimes combined. Persian Set adds the tarto a small Western orchestral ensemble. This is a beautifully shaped, double-bellied, three-stringed Persian instrument of very elaborate technique, for which the mandolin is an approximate substitute. (A guitar is used as substitute in this recording.)

“Persian music is modal (usually tetrachordal) and its modes rather persistently take either the note C or the note D for their tonic, as I have done here. There are five tetrachords in customary use which Iranian musicians combine in a number of ways. Four of these are used in Persian Set.

They correspond quite accurately to our tunings for (descending): C-B-A-G; C-Bb-A-G; C-B-Ab-G.

The fifth tetrachordal form has the famous quarter-tone interval at one point, and it is used just as much as the others, but one hears many pieces without it. It corresponds to the Western C-BbAhalf-b-G (not used in this composition).

“This quarter-tone is blamed by Iranian musicians for the difficulties in “modernizing” Iranian music by “harmonizing” it, but an even more basic trouble derives from the fact that it is not yet generally understood in Iran — what we in America have discovered only recently ourselves — that classic European harmony fits scales but not modes, whether the modes be those chosen for development in the Orient or in the Occident.

“One of the traditional musical styles heard in Iran today is a quiet, improvisatory one, arhythmical, like a prose invocation. Traditional Persian music was a great classic art which is said to have spread westward into many parts of the Arab-speaking world, reaching Greece about 600 B.C. In the 7th century A.D., the Arabs returned it to Persia in somewhat altered form as Islamic music. Moslem distaste for music had much less effect on the peoples of Iran than it did upon the Arabs, so that the practice of the art of music was never quenched in Persia after the Moslem Conquest. A few melodies surviving today are believed by Iranian students to be pre-Islamic, and certain types of mordents, and particularly the trill across a tone and a half, widespread today over the whole Middle East, are commonly called “Persian” by musicians of other countries. The elaborate Persian drumming techniques have been admired for generations, and even today in Cairo, Beirut and Istanbul most drummers will claim to be Persian —and sometimes are.”

Sources: